and Belize Inlets

and Belize Inlets and you will find steep-sided fjords,

raging waterfalls, quiet lagoons, solitary anchorages,

Native pictographs, and views of snowcapped

mountains. But ask most cruising boaters if they have

been there, and they’ll ask, “Where’s that?” Tell them it’s

behind Nakwakto Rapids, and they recoil in horror,

“Oh no, I’d never take my boat there.”

Nakwakto Rapids connect Seymour and Belize Inlets to Queen Charlotte Strait. The second fastest tidal rapids in the world (the fastest is Skookumchuck Narrows in Sechelt Inlet south of Princess Louisa Inlet), a passage through the rapids can be intimidating.

Nakwakto Rapids connect Seymour and Belize Inlets to Queen Charlotte Strait. The second fastest tidal rapids in the world (the fastest is Skookumchuck Narrows in Sechelt Inlet south of Princess Louisa Inlet), a passage through the rapids can be intimidating.

Currents in the rapids reach a maximum of 11.5 knots on the flood and 14.5 knots on the ebb. Slack lasts only six minutes. Currents run so strong past Turret Rock in the rapid’s center that locals call it Tremble Island. The Sailing Directions: Discovery Passage to Queen Charlotte Strait and West Coast of Vancouver Island warns, “Mariners are strongly advised to navigate Nakwakto Rapids only at slack water. At no other time is it possible to navigate this rapid safely.”

A boat passing through Nakwakto Rapids must first navigate either Slingsby or Schooner channels, which go up either side of Bramham Island and meet at the rapids. In Slingsby, the northern of the two channels, currents run at seven knots on the flood and nine knots on the ebb. In a strong west or southwest wind on the ebb, conditions in the channel entrance and offshore can be rough. Currents in Schooner Channel, the southern channel, run at five knots on the flood and six knots on the ebb. Islands at its entrance protect it from strong winds and seas, but rocks and shallows require careful attention. Of Schooner Channel, the Sailing Directions warn, “It is not advisable to attempt this passage without local knowledge.”

As if those natural hazards aren’t enough, mariners also need to watch for log tows in Nakwakto at high-water slack and in Schooner Channel on the ebb. A security call on VHF Channel 16 is a good idea.

Except for logging facilities, this is an undeveloped area. There are no marinas, stores, or repair facilities. However, VHF radio reception, including weather and Canadian Coast Guard, is good. Port McNeill and Port Hardy both offer supplies and services and are only a day away.

My husband Steve and I had passed Seymour and Belize inlets at least ten times in our Annapolis 44 sloop, Osprey, before we stopped. In the summer of 2013, we were sailing by Slingsby Channel when Steve said, “We’ve got a flood and the wind is calm; let’s go in and see what the rapids look like.” Uneasy at the idea of approaching the rapids on an incoming tide, I protested. But Steve was determined.

As we motored up channel, eddies swirled across the water. Currents whipped past rocks at the edge of the channel, piling up on the upstream side of rocks and falling into dizzying vortexes on the downstream sides. I imagined Osprey sucked through the rapids, chewed up, and spit out as fiberglass shards.

Steve glanced uneasily at the chart spread out on the cockpit seat. “Maybe we’d better find a place to anchor.” He shoved the throttle forward and steered toward nearby Treadwell Bay, the engine going full bore as it strained to get us out of the current. I held my breath as the boat seemed to crawl across the channel, then sighed with relief as we finally entered the bay and its quiet water. We dropped anchor in the bay’s northeast corner. A few minutes before slack water, we raised anchor and motored out toward the passage. Sunlight bounced off calm water, highlighting Turret Rock and its collection of wooden signs nailed to trees by victorious boaters. I thought about what a race it would be to nail a sign on a tree in only six minutes.

Passage through the rapids looked easy. If we hadn’t had other plans, we would have gone through. Instead, we turned south and rode the ebb out Schooner Channel to anchor in Skull Cove.

From that experience we learned two things: It’s almost as important to plan your approach to Nakwakto as it is to plan your passage through it and, as with any tidal rapids, a successful passage is all about timing. That winter, we started planning for a trip there.

Seymour and Belize inlets resemble a hand with long fingers reaching inland. Belize Inlet stretches 25 miles inland; Seymour Inlet stretches 43 miles inland to the Seymour River Delta. In between the two inlets, Nugent Sound extends ten miles inland. Coves, lagoons, and still more sounds branch from the inlets.

Remembering that M. Wylie Blanchet, author of The Curve of Time, had braved the rapids, I reread her story. The day before her family went through, a fishing inspector scared them with a tale of going through the rapids 20 minutes late, losing his propeller, and ricocheting on and off rock walls in the raging current for three hours. Blanchet and her five children anxiously watched the current, worried that their clock might be wrong. “Weren’t we sillies,” Blanchet tells her children after an easy transit in calm water.

Kelp streamed seaward as we motored up Schooner Channel the next summer. Just out of sight of the rapids’ swirling dangers, we pulled into narrow Cougar Inlet and anchored to wait for slack-before-flood, forecast for 1857 hours. Only the slightest current flowed through this little tree-lined inlet. A rock wall painted with boat names told us many had waited here before us.

At 1830 hours we raised anchor and motored toward the rapids. We rounded the first corner to see Turret Rock surrounded by calm seas. We approached the Rock at three minutes before the flood. The water was smooth. As we passed the rock at exactly 1857 hours, water streamed by the island and we picked up speed. I barely had time to snap photos before we were through. We turned north into Belize Inlet and I looked back at Turret Island, still surrounded by flat water. Steve and I looked at each other and laughed. A dangerous passage had been uneventful, the way it should be.

We’d made it through. Now we had a week to explore the secluded sounds and inlets of the Belize-Seymour Inlet area.

As we motored east up the long east-west arm of Belize Inlet the next day, I couldn’t shake the feeling that we were climbing toward the mountains ahead. At the entrance to Alison Sound, a half dome towered over the inlet. Below it bare black cliffs lined the shore. We turned north and followed a passage into the Sound past more black cliffs. But we were looking for light-colored cliffs, the site of a native pictograph reported to be in this area.

“There, just above that small tree,” said Steve, pointing to a spot about 20 feet up. A plain drawing in red ochre of six small canoes facing one large one, all clear and bright as if recently painted, was visible on the cliff. Archaeologists believe that this pictograph depicts an attack by Nakwaktoks, the local First Nation, on a trading ship. Another pictograph, in Belize Inlet, may depict a subsequent reprisal by traders in 1862.

We continued on to the end of Alison Sound where we dropped anchor off the mouth of Waump Creek with a view of verdant green marshes, forested hills, and rock bluffs. Later that afternoon, we took the dinghy up the creek. Waterlogged stumps crowned with flowers stuck above the water like little islands. It was comparable to cruising in a lake.

Rain persuaded us to stay two nights in Alison Sound. We puttered around the boat, enjoying the view from our port lights. We left in clearing fog and motored into Nugent Sound, where we anchored off Nugent Creek. Old pilings topped with ferns and flowers marked the site of a cannery that operated here in the early 1900s. A trail leading along the creek gave us a pleasant hike through a second-growth forest.

Osprey pushed easily through a one-and-a-half-knot current in Eclipse Passage into Frederick Sound. We’d planned to anchor in Salmon Arm, extolled for its views of high peaks and the grassy banks of the Tatz River. But as we approached the arm’s entrance, a puff of dirt arose from the shore, followed seconds later by a boom. A logging company was blasting roads. We turned Osprey south, away from Salmon Arm, to the head of Frederick Sound.

Steep cliffs towered above us as we wound our way to Frederick Sound’s head and its protected basin. An almost bare rock dome rose on one side, forested hills on another. A green marsh spread out at the Sound’s head. The Hamiltons’ guide noted a logging camp there, but the only evidence of it was a large pile of slash, a row of abandoned fuel barrels, and a small floating dock. It wasn’t pristine but was still beautiful, and we had a dinghy dock all to ourselves. We spent two nights there enjoying the warmth of a sun-heated cove and hiking on a logging road.

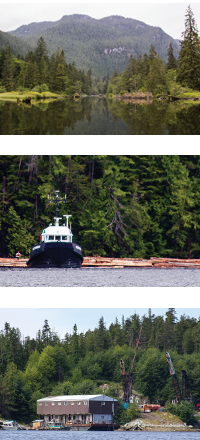

In our week of cruising in Seymour and Belize inlets, we saw many reminders that we were in logging country. In Belize Inlet we passed a tugboat assembling a large log boom. Entering Mereworth Sound, we passed an old-fashioned logging camp with rows of floating homes for loggers and their families. Logging companies once towed these from one logging site to another. A less organized version of a logging camp occupied the shores of Strachan Bay: brightly colored float homes and dilapidated trailers on floats tucked into nooks along the shore. And just about everywhere we went we passed barges for workers’ housing, equipment on the shore, and log skids on the beach.

In our week of cruising in Seymour and Belize inlets, we saw many reminders that we were in logging country. In Belize Inlet we passed a tugboat assembling a large log boom. Entering Mereworth Sound, we passed an old-fashioned logging camp with rows of floating homes for loggers and their families. Logging companies once towed these from one logging site to another. A less organized version of a logging camp occupied the shores of Strachan Bay: brightly colored float homes and dilapidated trailers on floats tucked into nooks along the shore. And just about everywhere we went we passed barges for workers’ housing, equipment on the shore, and log skids on the beach.

Logging camps park in one spot for a few years, then move on. No guidebook can keep up with their movements. Boaters must be prepared to share an anchorage or move on. Seymour and Belize inlets are part of the Great Bear Rainforest, but are designated Timber Supply Areas subject to ecosystem-based management. Only the Waump Creek watershed is protected from harvest. Small clear cuts dot the hills and snakelike rows of deciduous trees mark old logging roads, but the inlets are still beautiful.

Lagoons in the Seymour-Belize complex offer miles of quiet waters, separated from main inlets or sounds by narrow entrances and fast currents. Curious to explore at least one, we chose Nenahlmai Lagoon branching off Seymour Inlet. Both the Hamiltons and the Douglasses, authors of reliable guidebooks, had taken their boats through the Nenahlmai Narrows, and we thought we might be able to do that also. But one look at the raging narrows convinced us that even waiting for slack wasn’t safe enough for a deep draft sailboat, so we anchored and took the dinghy to explore.

The outboard roared as Steve put it up to full throttle, but the dinghy remained in place – the outboard was no match for the ebb pouring out through the narrows. Steve started to turn the dinghy to return to Osprey when I saw a riot of orange below the water’s edge. “Starfish!” I shouted, excited to see so many sea stars when the sea star wasting disease had almost decimated their populations in the Salish Sea. Steve gunned the outboard again and drove us as close to the shore as he dared. A thick band of orange sea stars lined the edge of the narrows, just above them ran a band of blue-black mussels. The mussels were feasting off the plankton in the current, and the sea stars were feeding off the mussels.

While we photographed the starfish, the current slowed. We turned the dinghy and headed into the lagoon. Trees hung over the water only inches from the surface. Small islands dotted the shoreline and knobby hills rose behind it. The lagoon stretched several miles inland. Bamford, McKinnon, and Whelakis lagoons branched from it. A small shallow draft cruising boat could venture in and have several days of exploration.

We returned to Osprey. Later that afternoon, we motored out of Nenahlmai and back into Seymour Inlet, heading toward Nakwakto and civilization. On our way toward the rapids, we passed several coves and bays suitable for anchoring. I wanted to call, “Wait! There’s more to see.” We would have to come back.

Because of the time it takes for the water to exit Nakwakto Rapids, the times of high and low waters are two to three hours later inside Seymour and Belize inlets than outside. And the tidal range inside the inlets is less than outside: 2m (6.6 ft) in Belize Inlet, for example, compared to 3.7m (12.1ft) in Treadwell Bay in Slingsby Channel.

Volume 6 of the Canadian Tide and Current Tables covers this area. Nakwakto Rapids is a current station: you can read times of slack and maximum currents and current speed right off the table. You do have to add an hour for Daylight Savings Time.

Schooner and Slingsby channels, the entrance to Nenahlmai Lagoon, and Eclipse Narrows are all secondary current stations referenced to Nakwakto Rapids. The Tables also give you conversions for time and height of high and low waters for seven secondary tide ports in the Seymour and Belize Inlets area.

The Tide and Current Tables don’t answer all the questions a boater might have about the currents in the region. For example, they say nothing about currents in the NS-EW reach of Seymour Inlet adjacent to Nakwakto Rapids. Logic told us that when the rapids are ebbing, currents in that reach should be flowing out toward the rapids and when the rapids are flooding, currents in the reach should be flooding in. We found the opposite as did some friends of our who had been there several years before.

We have learned to be cautious when using other than official Canadian Tables. We carry a tablet with a popular tide app. In checking this against the official tables, I was horrified to see its forecast for slack water at Nakwakto was sometimes as much as ten minutes off the official forecast. When slack lasts only six minutes, ten minutes can be the difference between an easy passage and a nail-biter. The app recommends, “when in doubt consult the official tide publications for your region.” That’s good advice when using any app or nonofficial publication.