The University of Washington is racing against time in a bid to restore the historic, 1918-era Shell House on the Montlake Cut, once home to the Olympic champion team of Boys in the Boat, racing shell builder George Pocock, and countless crews that have rowed our waterways.

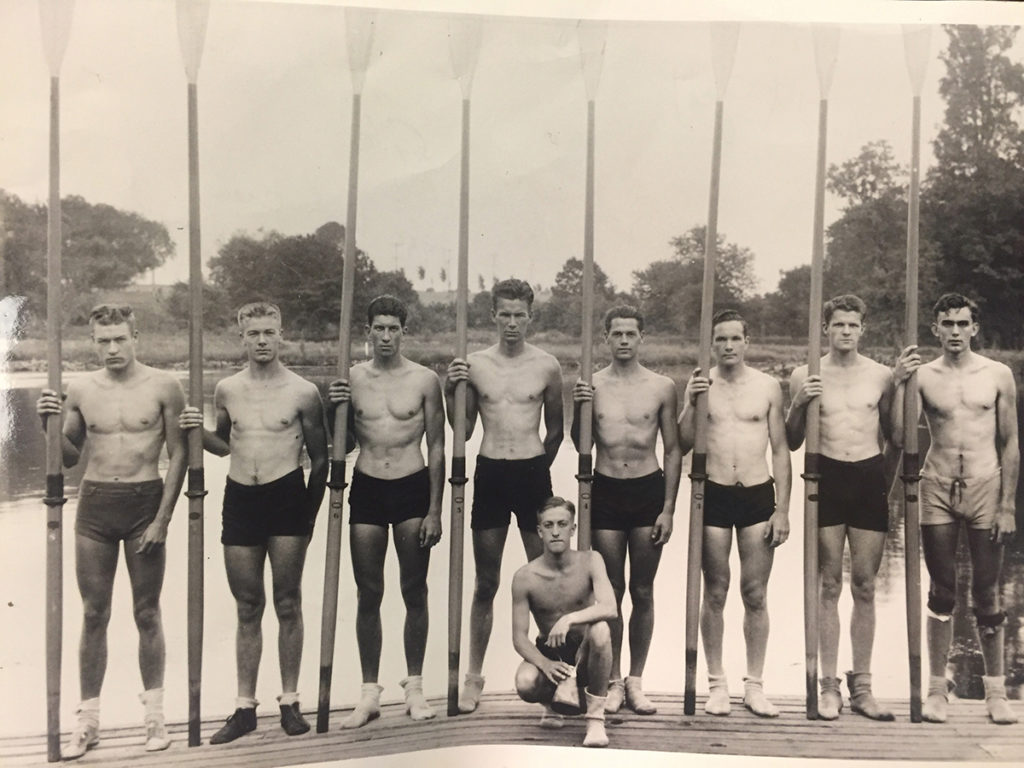

Just twelve short pages into Daniel James Brown’s #1 New York Times bestselling book The Boys in the Boat, which chronicles the real-life story of nine members of the University of Washington men’s crew and their inspiring quest for gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, readers are introduced to the tenth character in the tale. This all-important supporting cast member is not a person, but rather a building—the ASUW Shell House, home to those now-famous boys and the collegiate crews that came after them and the workshop for famed racing shell builder George Y. Pocock. Not to be lost in the past, the Shell House is now inspiring a grassroots movement to preserve and rejuvenate the historic site so it can be enjoyed for generations to come.

Tucked along the lapping shores of the Montlake Cut on the edges of the university campus in Seattle, the World War I hangar was originally built in 1918 by the U.S. Navy. Its purpose was to store seaplanes and act as a training ground for budding aviators, but the Great War ended before it was fully used. The building was turned over to the university in 1919, and given its proximity to the water, the college’s rowing teams adopted it as their home base.

Over the next hundred years, the sight of the UW crew making their way up the Cut, stroke by precious stroke, would become as synonymous with the city of Seattle as the Space Needle, Mount Rainier, and both Union and Washington lakes.

“The spirit of this place is incredible,” says Nicole Klein, the capital campaign manager for the University’s The Next 100 Years initiative now leading the charge for restoration. “The sounds and smells here give you an immediate sense of place. You can hear the seaplanes flying over, boats idling by, geese honking, a coxswain yelling commands on the Cut… There’s this smell of lingering sweat, the bright sunlight streaming through windows, an almost palpable presence of history.”

That history is long and rich. The Shell House played an integral role in the story of that 1936 team that ultimately won gold—it was the place where they built camaraderie and confidence under the tutelage of coach Al Ulbrickson. The upper loft is the stuff of legends, a sparse space once filled with the smell of wood shavings as George Pocock labored away on his renowned wooden racing shells crafted from Northwest-felled timber. From here, Pocock built a racing dynasty, his shells dominating consecutive Olympics to garner 21 gold medals from 1920 to 1964 (wooden shells were replaced by fiberglass ones starting with the ‘68 Olympics). Yet another UW crew rowed from here and won gold in the 1948 Games. It was also the original home to the Lake Washington Rowing Club (LWRC), whose illustrious women’s team won the first-ever National Women’s Rowing Association Championship in 1966, and then again in 1969.

But, during the early 80s, the building fell into disuse. The crew and Pocock had moved to the new Coniber Shellhouse at the far north end of Union Bay near Husky Stadium in 1949. It then spent 30 plus years known as “The Canoe House,” hosting the LWRC. A family even lived upstairs for a while, renting out vessels for students to venture out on the Cut. In 1976, the Waterfront Activities Center opened and vessel rental activity was headquartered there, and the Shell House was relegated to boat storage.

Dust gathered, the doors were rolled shut. The distinct frontage became a familiar landmark to yachters cruising past to tailgate at football games, a quiet giant that overlooked the kayakers and canoeists paddling by. Even after an era sitting at slumber, the Shell House today still closely resembles the iteration that Joe Rantz, the primary subject in The Boys in the Boat, first laid eyes on during the inaugural day of tryouts in 1933; the weathered, shingle-clad exterior walls pitch inward as they rise, drawing the eye up to the unique gambrel-style roof. At water level, two enormous sliding doors, the upper halves adorned with massive windows, open to reveal an interior defined by soaring wooden beams and sun-dappled concrete floors. In ‘33, a wide wooden ramp ran down from the doorway to a launch dock for the shells; nowadays a much narrower path leads directly into the Cut.

When The Boys in the Boat book debuted in 2013, it was a sensation. The rights were quickly optioned for a movie, drawing national and international attention to the Shell House, and bringing fans to Seattle (these eager tourists even inspired a local The Boys in the Boat tour). That all prompted discussions amongst University staffers, with then-new Recreation Director Matt Newman asking: Why wasn’t this historic building being better utilized, both by the university and by the community at large?

Photo Courtesy of Blue Sky Photography

Photo Courtesy of Blue Sky Photography

Thus was born The Next 100 Years campaign, the University’s $13 million initiative to restore the historic hangar. Klein, who had been involved in fundraising at the university since 2006, came onboard the project in 2017. She has spent the past four years working towards building the plan for the future and raising the funds that would allow the university to create what they envision would be a flexible, multi-use space; one used for special events and gatherings, but also that acts as a “welcome mat” and historical cultural center for the public to come, learn, and reflect. “It will truly be the ‘front dock’ to the UW campus–greeting students, and welcoming the public to experience our rich and complex waterfront history,” states the campaign’s website.

In 2018, the building was granted historical landmark status by the city as it celebrated its centennial birthday. The team has since worked with design firm SHKS Architects on the initial feasibility studies and renderings, with both parties working towards preserving what makes the facility so special already. “The goal of the restoration is to preserve the magic, the patina, and the authenticity of the building as it is,” Klein explains.

The plans include restoring the historic Pocock loft, dedicating that and other additional space to the display of historic boats and informative exhibits on the local military, aviation, rowing, and sailing stories the building holds dear. They expect to draw in first-time Seattle tourists, curious locals, prospective and current students, fans of the book and the future movie, and even draw from the many Pocock aficionados found in this rowing-savvy region. (Look no further than Port Townsend’s Rat Island Rowing & Sculling Club, a group of purists that rows almost exclusively on the antique Pocock creations that have found their way to the clubhouse.)

Other key features will include a café; a classroom for student use and lectures; gift shop; and an expansive open events space available for rental. The signature sliding doors will be restored to full working order, rolling open to create outdoor access across a stunning 65-foot-long expanse open to the water.

After a pandemic lull that prompted the halt of the popular tours and with the much-anticipated movie mired in production delays and changing of hands, it seems as if the project is poised to gain a stroke or two here shortly. After being recently acquired themselves by hometown Amazon, MGM Studios now controls the movie rights and the script. And, none other than A-list star George Clooney is set to direct the feature film with his production company Smokehouse Pictures alongside producer Grant Heslov. (The film release date was TBD at press time, but is expected to start filming next April.)

But there’s much work left to be done: The campaign is well shy of the $10 million needed to start construction, and that goal needs to be fully funded by next June in order to move forward.

Klein points to a story woven into the very fabric of the Shell House story as a source of optimism. In 1936, the UW boys were complete underdogs in Berlin. It was an Olympics that, much like the one currently occurring in Tokyo, was fraught with anticipation, not caused by a pandemic-related pause as now, but by burgeoning tensions in Europe due to the rise of the Nazi party in Germany. For Hitler, the Games were supposed to be a show of German strength and superiority, and the young, scrappy Americans had no place in the plan. The boys rowed through a political firestorm, drawing the far outside lane for the race, balking at the start after missing the flag drop, and even powering through stroke Don Hume almost passing out during the leg. “And yet, they prevailed,” Klein says with a smile.

Back in 2013, it was much ballyhooed that the book saved the building, but in 2021, Klein now hopes it will be the community that rallies around the cause to restore it. “This building has a heartbeat, a soul, and layers and layers of story to it,” Klein concludes. “And it’s a heart that deserves to keep beating, for the university, for the city, and for all of us.”

For more information on the ASUW Shell House, or to give to The Next 100 Years Campaign, visit asuwshellhouse.uw.edu.