When we finally sold our beloved Cape Dory sloop, Peponi, several years ago, I volunteered to deliver her from Seattle to her new owner in Olympia. We took her out for a sunset sail the night before I left. A crisp northwesterly wind blew all evening as we tacked and jibed our way around the Puget Sound with no destination.

When we finally sold our beloved Cape Dory sloop, Peponi, several years ago, I volunteered to deliver her from Seattle to her new owner in Olympia. We took her out for a sunset sail the night before I left. A crisp northwesterly wind blew all evening as we tacked and jibed our way around the Puget Sound with no destination.

At one point I set her on a beam reach, trimmed up the main a little bit, and left her to steer herself, which was one of the reasons I loved that boat so much. She was perfectly balanced under sail. I made my way to the bow and stood forward of the headstay, listening to the sound the water made as the bow cut through the chop.

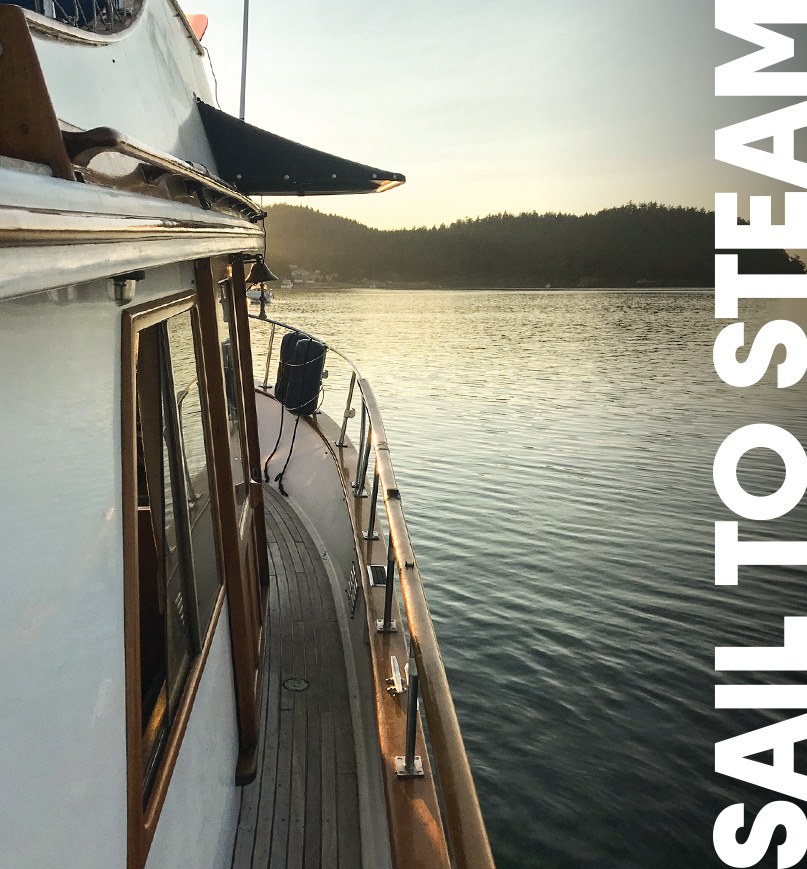

The next morning, all signs of the previous evening’s breeze were gone. Puget Sound was mirror calm as far as I could see. It was late April, but the forecast was for sun and calm winds. My farewell cruise on Peponi was going to be a long steam south, not the solo sailing adventure I had hoped for. I should have expected it.

And today I’m glad for it. Having to motor my way south past Tacoma and through the Narrows, and around the labyrinthine channels of the South Sound confirmed our choice. We were switching from sail to power. The time had come.

The true age of sail gave way to the age of steam sometime in the late 19th Century, when naval powers began modifying or rebuilding their fleets with either auxiliary steam engines or dedicated power plants. Notably, the British HMS Devastation (not a subtle name, that one) became the first battleship to enter service without sails of any type. Steam-powered ships and tugs had been in service long before this, of course, but they were typically used in short service, on protected waters, or transiting the canal systems of Western Europe. Sailing ships were equipped with small steam engines as auxiliary power, but ships capable of making long crossings on steam power plants were the ultimate goal.

The advent of oceangoing steam vessels changed naval warfare and commerce forever. No longer wed to the predictable tradewind routes across oceans, and free to maneuver in harbors and narrow channels, ships delivering goods around the world became faster, more efficient, and less likely to be plundered by pirates lurking at the end of the well-worn highways across the oceans. Naval powers launched ironclad ships with all manner of power plants, but coal-fired steam was long the engine of choice.

For crewmen, the switch to coal-powered ships was not necessarily an upgrade. Coal was dirty, heavy, and dangerous. Below decks on one of these early naval ships was a dark, dangerous place. The use of a finite fuel source limited the range and course of these ships.

Sure, they were no longer stuck on the same tradewind routes, but they could only go as far as their onboard fuel supply would allow. And, importantly, they could only take on new coal stores in limited locations. Pirates and military adversaries took advantage of this new limitation in largely the same way they did the tradewind routes.

Still, it is impossible to catalog the advances in naval tactics and shipping efficiencies born from the widespread adoption of the steam engine. The Suez and Panama canals came online. Narrow harbors all over the world became viable trade ports. Speed, efficiency, and power quickly made the remaining sailing ships a quaint reminder of the past.

Sail power remained the number one option and choice for recreational boating for many decades after sails were completely forgotten by commercial shipping, however. Obviously, sail power persists today for cruisers and racers. Take a look at your local marina and try to count the masts in the forest of aluminum.

I grew up on sailboats. We never owned a boat – my parents decided to spend money on food and heat instead, I guess – but we had friends who did. I was eight years old when my dad took me with him to a race off of Shilshole. His friend Tim had a Ranger 22 that was magic to me.

I still have visceral memories of the little motor being shut down and the mainsail popping full of wind as we tacked around the starting line. I knew nothing about sailing except that I loved it. Instantly. Tim was a terrible sailor. More than once we sailed back across where the finish line was supposed to be, only to find that the race committee was already back at the bar. I didn’t care. Racing didn’t matter.

I spent my library time at school looking for books about sailing. I drew pictures of sailboats on my notebooks. At home, I built sailboats out of Legos, eventually figuring out how ballast worked when I taped a fishing weight to the bottom of my plastic creations. I made sails out of aluminum foil. The bathtub regattas were epic after that.

This is all to say that I loved sailing. And I still do. But we’re a powerboat couple now. Our own age of sail came to an end with an abrupt decision to sell Peponi and get into the trawler life.

I grew up on sailboats. We never owned a boat – my parents decided to spend money on food and heat instead, I guess – but we had friends who did. I was eight years old when my dad took me with him to a race off of Shilshole. His friend Tim had a Ranger 22 that was magic to me. I still have visceral memories of the little motor being shut down and the mainsail popping full of wind as we tacked around the starting line.

I knew nothing about sailing except that I loved it. Instantly.

Tim was a terrible sailor. More than once we sailed back across where the finish line was supposed to be, only to find that the race committee was already back at the bar. I didn’t care. Racing didn’t matter.

I spent my library time at school looking for books about sailing. I drew pictures of sailboats on my notebooks. At home, I built sailboats out of Legos, eventually figuring out how ballast worked when I taped a fishing weight to the bottom of my plastic creations. I made sails out of aluminum foil. The bathtub regattas were epic after that.

This is all to say that I loved sailing. And I still do. But we’re a powerboat couple now. Our own age of sail came to an end with an abrupt decision to sell Peponi and get into the trawler life.

The lore is that sailors give up their boats for power boats as they get older or as they or their partners lose the ability to work the lines and move around on deck. Some get tired of waiting for the wind. Others, like my neighbor at the marina, find a little more money in retirement and can finally afford to upgrade to the larger power yacht they’ve always wanted.

Our switch happened fast, and the decision to do so seemed abrupt, but it was a long time coming. It was born of the sort of discussion that would make a marriage counselor proud.

Peponi was our boat on paper, but it was my boat. I found her. I did the research. I rebuilt her. My partner, Hayden, loved the boat and enjoyed sailing with me, but the boat never felt like hers, and while Peponi ably took us wherever we wanted to go, it was never truly comfortable as a cruising platform. We found ourselves–against type–spending more time onshore at bars and restaurants than we did sitting on deck sipping our own wine and eating our own snacks. Hayden never loved the idea of being down below on a sailboat in the few sunny months we have here in the Northwest.

Importantly, we found that we rarely actually sailed our sailboat. In this way I think the sailing gods were watching after my ego and my heart a little bit as I set the autopilot and motored Peponi south toward her new owners. If it had been windy, I would have taken my time and squeezed every bit of sailing I could out of her along the way.

And that would have been the memory I had as I walked away from her the next day. Instead, what I remember is exactly what I know to be true about our time with that sloop. We spent more time motoring in no wind or against currents than we did making perfect crossings of the Straits of Juan de Fuca on an afternoon breeze.

Two weeks later, I was back in Olympia. By sheer coincidence, the trawler we bought was located just a few slips away from where I had delivered Peponi. Other than the sea trial, I had zero experience on large, single-screw power boats. I found everything about our new 34-footer intimidating, not least of all the feeling of unease at only having the one engine and no other way to move the thing.

Though it never happened on Peponi, I had been caught on the water with a dead engine on a previous sailboat and being able to sail back to the dock gave me comfort.

Still, here I was, piloting a boat that seemed far too large, with a big engine and no sails. I overworked the thrusters to get out of the slip with zero subtlety or finesse. I tried to remember what the previous owner told me about the systems and how hard to run the engine. Something beeped at me for a few minutes. I felt too high up on the flybridge, like I was somehow upsetting the balance of the boat. For the first hour or so of the delivery trip, I had nothing but feelings of regret.

This big old powerboat wasn’t my scene. Until it was.

A month or so later, Hayden and I filled the fuel tanks and set off for the Gulf Islands. We cruised at a comfortable 8 knots and sat on the flybridge sipping coffee. We moved around the deck and cabin easily. We spread out. There was room for all of our stuff. The galley was well-stocked. It was bright and airy down below. At one point, I set the autopilot and went below to find that Hayden was settling in. Unlike on Peponi, she was moving aboard and making the space her own.

A little breeze came up as we crossed the Straits of Juan de Fuca for Cattle Pass. Had we been on Peponi, I would have raced to get the main and jib flying. Instead I just watched as the wind ripples spread across the otherwise calm water. In ten minutes, the wind was gone.

I would have been left powering along with the sails uselessly flapping around, until I dropped them onto the deck, hoping for another breeze to fill in. Instead we powered along, slowly but surely, toward our destination. If this were a storybook tale a whale or at least a porpoise or two would have surfaced right then, but life can’t be perfect…

I am still young enough to sail, and I still take any ride offered on a racing boat in the Puget Sound (did you hear that, readers? If you need a decent hand in the cockpit for a race, give me a shout). I have thoughts of maybe getting another small sloop, so I can scratch the sailing itch when it strikes me, but I must say that I truly love cruising slow on our powerboat.

The advantages for us are hard to overstate, and the fact that Hayden considers this boat “ours” instead of “mine” is chief among those advantages. We named her Kokua, Hawaiian for “togetherness, help, or cooperation.”

I also still marvel and the grace and beauty of a nice sloop. I can pick out most designers and brands from a distance, and I still walk the docks and dream about taking a classic sailboat across an ocean. But I have also come to find a lot of the modern slow-cruisers to be true beauties. I appreciate recreational trawlers and tugs far more than I ever thought I would, and when I window shop for our next boat it is trawlers, not sailboats, that I am looking for.

Historically, the shift from sail to steam was one of necessity and competitive advantage. We are under no such pressure, and many of us will cruise under sail for as long as there is water and wind, but I can tell you from experience that the shift from a lifetime of sailing to a second chapter strictly under power can be a smooth transition.

Read the print version on Issuu