As a marine journalist, I’m well acquainted with the concept of the “P.R. Cruise,” which has emerged as the single best way to roll out a new boat build to the world.

As a marine journalist, I’m well acquainted with the concept of the “P.R. Cruise,” which has emerged as the single best way to roll out a new boat build to the world.

The formula is simple; take a shiny new boat on noteworthy adventure and invite as many nautical writers as you can. It’s a win-win-win situation for boat builders, writers, and readers, as one of the big obstacles to writing a compelling boat article is finding a good narrative to hang all the specs and breathless prose on. Throwing an adventure in the mix gives those stories much-needed life, allowing the writer to explore the cast of characters aboard and intricacies of the wild waters ahead.

With the P.R. Cruise approach, the writer and reader both experience the true thrill of exploration and touch on the deeper answers to why we boat. Or, ideally for the manufacturer, why we should fall in love with their boat.

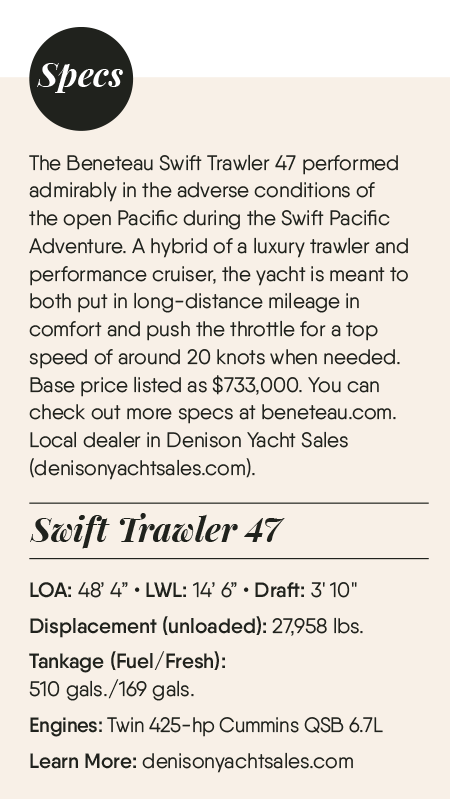

I arrived in Newport, Oregon, on a first date with Beneteau’s all-new, hull number one of the Swift Trawler 47 (ST 47). I had a berth aboard for a leg of Beneteau’s Swift Pacific Adventure, an ambitious whirlwind tour from Seattle with stops along the West Coast down to San Diego.

The trip was to culminate in a glorious debut of the yacht at the San Diego Boat Show, where not only would she look nice at the dock but have a big-water adventure to boast about. As one may expect while charting such an adventure, the legs between the Pacific Northwest and San Francisco Bay were the longest, as the beautifully rugged but potentially dangerous coasts of Washington, Oregon, and Northern California are not places for boats to loiter.

As I should’ve expected, other magazine writers had nabbed the short, pleasure cruise legs. San Francisco to San Jose, a sunny 50ish nautical miles. Los Angeles to the Channel Islands, a scenic 75 nautical miles. My leg in the open Pacific from Newport to San Francisco? Approximately 620 nautical miles.

The cherry on top is that I was the only writer aboard, so the adventure would be just me and the skipper, a seasoned and highly recommended fellow named Jackson Willett. I privately dubbed my leg the Hero Leg, although I had to tip my hat to my peers. They knew a thing or two about self-preservation and maintaining a quality of life.

In my search for the transient dock, I ran into a gray-haired gentleman gazing out toward the bar entrance. His was the weathered face of a local sea salt, and I asked him for directions.

“Just go ‘round a bit further that way,” he assured me. I picked his brain a bit about the weather. “Oh, there’s something foul rolling in soon. There’s a halibut derby comin’ up and we’re all not sure how that’s gonna go. This weather is only good for trailer sailors.”

I thanked him and had a hunch that Beneteau’s best laid plans might need to yield to the Pacific’s whims. I was reminded of the advice—Go with the weather, not with a calendar—from delivery captain and Northwest Yachting contributor Captain Chris Couch, who specializes in delivering yachts on this very run.

At last I came up on the ST 47 and it was easy to understand the popularity of the yacht at a glance. Styled to look sleek and modern instead of nostalgic and brassy, the Swift Trawler 47 certainly looks like trawler with a beamy (but not overly so) figure, near-plumb bow, and hard cover flybridge.

The foredeck features a large padded sun lounge area and the aft, a generous swim step—both made for sunny days in Puget Sound, not overcast stormy ones on the open Pacific. The emphasis for the ST 47, and most boats, are for facilitating fun in the sun. Would this pretty, French trawler with its luxury accoutrements be up to the challenge?

As I approached, two writers were eagerly hopping off from two days aboard, their belongings already strewn about the dock and their stories, embellished with grand arm gestures, told over cell phone conversations with loved ones. Captain Jackson Willett appeared.

“We’ll introduce ourselves properly later,” said Captain Willett after a quick handshake. He, like all the good captains I know on the job, was juggling a hundred variables in his mind. “Bad weather is coming in and we’re going to make a run for Coos Bay today. We’ll wait for a weather window to continue. Slack tide is at 1600 hours and we got to make it to cross the bar.”

“Sounds like a plan, skipper,” I saluted. “I talked to a halibut fisherman on the way over and he said the same thing about the weather.” Captain Willett nodded.

“Yep, might as well get as far south as we can. We’ll probably be waiting in Coos Bay for a few days, but we should still make the San Diego Boat Show debut.” We weren’t on the dock for more than

15 minutes before we were off. I stowed the fenders and dock lines as Captain Willett rocketed onto the Pacific, the Yaquina Bay Bridge in our wake. It was Coos Bay or bust.

Even this early in the trip, I started to appreciate how easy it was to get from one side of the boat to the other, partly thanks to the huge, open salon space and wide, sheltered side decks. The fenders and lines stowed easily under the floor of the covered cockpit, along with most of the other more cumbersome items. A uniquely Oregon coast gray, a new crayon color I’m workshopping, set in so it was hard to distinguish sea from sky. We were in the wild, gray yonder.

We set in for the trip and I dutifully started taking notes on performance. Captain Willett’s favorite driving spot was clearly the flybridge, which was comfortable and provided great visibility. Since time was of the essence to make the Coos Bay slack tide across the bar, Captain Willett was going close to full throttle and the twin 425-horsepower Caterpillar inboard diesel engines yielded a speed of around 17 knots.

What really made it a ride was the eight- to ten-foot following swells, and the ST 47 reached sustained bursts of speed of around 21 knots. With zippy performance like this, I felt less like I was on a trawler and more like an express cruiser or other trawler-adjacent category of boat. The ride was easy with minimal hobby horsing.

While there is a trendy movement in yacht design to eliminate the cabin helm and keep the single helm and nav station up on the flybridge, the ST 47 resists this. The main benefit of the single flybridge helm is that it provides even more entertaining space in the cabin.

However, especially in an open flybridge model like the ST 47, having the ability to drive from within the cozy interior is still popular with boaters. The interior is plenty large, even with a helm station.

“Keep an eye out for crab pots,” Captain Willett asked, and together we diligently scanned the waters ahead and dodged countless small, bright floats which look innocent enough to a layperson, but would mean wrapped props and worst-case scenarios to boat captains. We finally danced our way out of the crab pots, and as a few hours ticked by, we began to relax. A whale puff in the distance was taken as a good omen.

Thanks to the Pacific’s generous following seas and the ST 47’s sporty performance, we were making great time and we’d even had to slow a bit to time the slack tide bar crossing in Coos Bay correctly. Captain Willett and I kept up our vigil for crab pots and potential obstacles, but we finally got around to that proper introduction.

“I run a powerboat school and charter company out of Newport Beach (California),” said Captain Willett. His was a sea salty life with charter companies on the East Coast, Hawaii, and ports in between. “I was living on my Grand Banks 36 in Newport Beach and taking people to the Channel Islands so much, I figured I might as well do it for a living.” His company, Newport Coast Maritime Academy, is a demanding but rewarding endeavor. This trip was his first chance to run down the West Coast and he jumped at the opportunity to add the notch to his belt.

“I’ve been calling this the Hero Leg,” I said. He chuckled.

“Sounds about right to me.” We were about seven nautical miles off the coast of the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area when bits of debris started to muck up the previously clear ocean. I knew the mouth of the Umpqua River was somewhere nearby, one of the most beautiful rivers in the world in my opinion.

We kept our eyes strained for anything troublesome. It was only a few more hours to the bar entrance. Surely, we had this transit in the bag—CLUNK! Va-ROOM-ROOM-ROOM! Something hit us and the port prop struggled as if caught on something for a few seconds.

“What the-?” I started as we looked behind. The scattered wooden remains of a mid-sized, mostly submerged log bobbed in our wake. We slowed to near idle. Apparently, the Umpqua River had sent us a gift.

“Take the helm! I gotta check that out,” said Captain Willett as he dashed below. I turned off the autopilot and did my best to keep to our bearing. More half-sunk logs floated into view. I dodged a big one. Captain Willett returned. “Port engine is out. It’s impossible to say how bad the damage is, but it’s looking pretty bad,” he said. I’ll omit a few mutual expletives here, the bar crossing suddenly not in the bag at all. I pointed off our starboard.

“The starboard engine is smoking for some reason,” I said.

“Yeah, we’ve had a slow diesel leak from that one and I’m planning to check it out in Coos Bay. I’m not too worried, typical new boat kind of problem.”

“Right,” I nodded, deferring to his expertise. “What’s the plan? If we miss that slack tide for the bar crossing, we’ll be a lame duck in the open when that bad weather rolls in.” Captain Willett took a few thoughtful moments.

“Did I show you where the life jackets and life raft are?”

After a brief but adequate safety orientation, Captain Willett and I ran some tests to see what kind of shape we were in. The port engine shook violently when pushed over 500 RPM, so we kept it below that. It was the smoking starboard engine’s big day to take us home, and the harder we pushed, the more smoke we put out.

We huddled again, and Captain Willett put me on engine monitoring duty as he took the helm and issued a sécurité to the U.S Coast Guard. With the Coasties monitoring our situation and the starboard engine giving us a respectable 10 knots of speed, our chartplotter was giving us about 30 minutes of wiggle room for our estimated time of arrival to the Coos Bay Bar and slack tide.

Notably, the onboard VHF system did not work as well as the skipper’s handheld, an important piece of feedback for Beneteau. Perhaps a longer antenna is warranted? I’d have to ask a technician.

I wrote down the fluid levels, temperature, RPM, and other engine vitals every five minutes for Captain Willett’s logs. I was to warn him if something spiked or dipped alarmingly. I felt like a nurse monitoring a patient’s vitals.

We kept in touch over the intercom, a system that worked very well and minimized yelling and shouting back and forth, bringing down the anxiety a notch. I also got well acquainted with the engine access, which essentially lifts the entire floor of the salon. For the purpose of reaching the engines, I’m not sure if it gets any better for a boat this size than the arrangement on the ST 47, although the positioning does completely transform the salon into a loud mechanic’s shop.

After a tense transit, we finally were in position to cross the bar into Coos Bay without time to spare. The seas, once friendly and following, were becoming sloppier and flat as the winds picked up. It was time to get in, and I joined Captain Willett at the helm on the flybridge. He handed me binoculars.

“Keep an eye for the markers, we’re going to want to line them up and get in there,” he said. I found them and we lined up. “Let’s do this,” he said and we limped in, the white water crashing on the breakwater to either side.

The seas became the sloppiest of all: following and quartering. Captain Willett deftly corrected course as the ST 47’s purchase became a bit slippery. It’s common knowledge that all boat designs are a series of compromises, and the shallow draft that makes getting up on step so easy shouldn’t be expected to thrive in rough seas.

I wouldn’t call it a deal breaker, but I’d avoid those following quartering seas as an operator.

We rolled into the Charleston Marina in Coos Bay and put the Coasties on standby at ease, we were now officially the dock talk of the town. We nestled into the transient slip among all-wood commercial vessels getting ready to chase albacore tuna as far as Midway Island. One proudly touted the year 1917 on its transom and flew a Norwegian flag.

The next few days were a whir of logistics and stretched legs between helpful marina and boatyard offices. Beneteau scored a lift in the Charleston Shipyard to get the prop checked out and I stuck around to help out Captain Willett.

Charleston is a tiny working-class community built around the commercial fishing industry, and we probably struck up friendly conversation with half the locals. There weren’t too many luxury, European yachts in the marina.

The days in Charleston gave me a chance to make the ST 47 a proper home. The accommodations aboard, including the excellent galley, always felt comfortable and get thumbs up from me as a crew/passenger. One point of feedback I’d give is that the two guest staterooms with berths are rather small, and I could see older guests or those with limited mobility shying away from the starboard one I resided in with its limited headroom.

In contrast, the master stateroom, complete with an island-style berth, is huge, which makes the ST 47 especially well-suited to a boating couple with guests just happy to be aboard or a family with children.

When the yacht was lifted, I got a good look at her underbelly. Turns out, the damage could’ve been far worse. The impact with the log left a small scratch in the paint, and the port shaft was spared severe damage. On toughness, I have to give the ST 47 high marks.

A simple prop replacement was in order, for three of the four port propeller blades were curled, not in a way that was obvious to a casual observer but clear upon closer inspection. Clearly, the log had wedged itself in there.

When Captain Willett and I finally left hull number one at the boatyard, I couldn’t deny the emotions I felt while bidding her au revoir from the rental car: appreciation, respect, and affection. She had done everything asked of her, even in trying conditions. Now here she was, seemingly eager to get back on the saltchuck for round two.

I was unable to join him, but Captain Willett finished the delivery in time for the San Diego Boat Show debut, now a plucky underdog success story.

As we left the yacht behind on stands among the commercial boats—some rusting away and others nearly ready to chase seafood again—I thought of her as a young French model, stranded in small town America after car trouble. Disorientated but glad to be safe, she wanders into a bar full of surly fishermen and millworkers fresh off the clock.

Rather than shy away or remain aloof in the corner, she sits with them, orders a round of whiskey, and drinks them under the table, somehow one of the guys despite her upbringing and the circumstances that brought her there. As the Cajun French saying goes: laissez les bons temps rouler!