There are many books devoted entirely to shipwrecks on the Pacific Northwest coast, especially at the notorious Columbia River Bar. One hundred miles inland, the maritime casualties around Portland have lacked the big waves, rocks, and loss of life on the western shore. That was the case in the loss of the Soviet cargo ship Illitch that sank in Portland Harbor on June 24, 1944, not with a bang, but a whimper.

There are many books devoted entirely to shipwrecks on the Pacific Northwest coast, especially at the notorious Columbia River Bar. One hundred miles inland, the maritime casualties around Portland have lacked the big waves, rocks, and loss of life on the western shore. That was the case in the loss of the Soviet cargo ship Illitch that sank in Portland Harbor on June 24, 1944, not with a bang, but a whimper.

This dramatic event was as close as Portlanders ever came to seeing the loss of a ship in wartime, though there was never any evidence that it was caused by sabotage. The cause was likely a mistake in ballasting, which happens occasionally even in the 21st century, or a leak in the 50-year-old riveted steel plates below the waterline. The story appeared in the Oregonian newspaper the next day and was followed by journalist Larry Barber over the next five months as the authorities decided what to do with the old ship.

After hearing the news, he was soon on the scene, where the side of the capsized Illitch was barely visible in the muddy Willamette River and surrounded by flotsam that had floated off the ship’s deck. Barber learned that a shipyard engineer had noticed the ship listing at about 0430 hours, and went down into the engine room and found “water boiling up into the bilge,” explained Tex Morrison, superintendent for Northwest Marine Iron Works.

The engineer called for portable pumps to be fetched, but ten minutes later chains, welding machines, and heavy gear all began sliding off the sloping decks. He ordered all his men off the ship and informed the Russian crew that the Ilitch was going down and they should abandon ship immediately. Within 30 minutes, the ship was on its side and the captain, chief mate, and about 20 members of the crew had clambered to the highest point of the hull to escape the water.

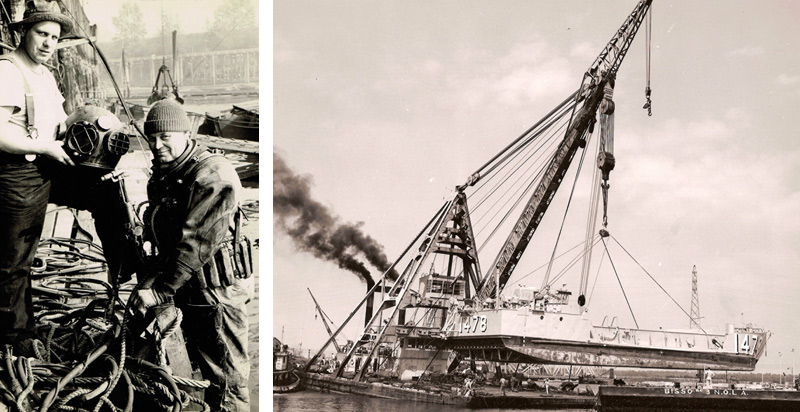

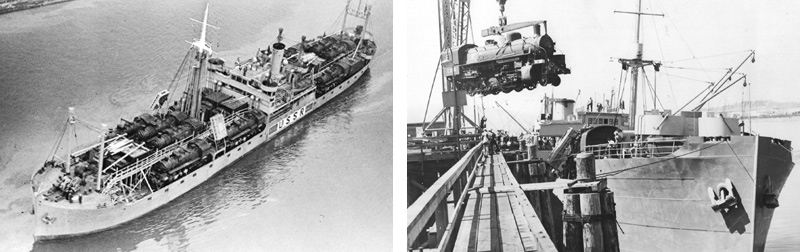

Above: The massive derrick barge Cairo hoists some of the Illitch‘s wreckage. The ship had to be broken up quickly to make way for more ships and for Liberty ship production. The process took five months.

Some were rescued by means of a “cherry picker” basket on a mobile crane while other climbed up a rope ladder that had been lowered by men on a Liberty ship in the next berth. A total of 58 crew escaped before the ship rolled over at about 0500 hours. When the roll was called on shore, only the 20-year old female cook, named Agreppina Arakhpaeeva, was missing.

The Illitch settled slowly onto its side in 45 feet of water. Not only was the hull blocking the dock, which was used for repairs to visiting ships and fitting out newly-launched Libertys, it was also obstructing the port’s main drydock and preventing it from being used. This was a serious obstacle to the smooth flow of work in the Kaiser yards and needed to be removed as soon as possible.

The Illitch was not going to surrender without a fight and presented a problem that stumped the best efforts of the local maritime community. With new ships being launched in the Rose City every few days, the sinking of a 50-year-old Russian ferry was no more than a footnote in the big picture of the war effort. Many of these ships had been pressed into service regardless of their age or condition, and appeared to date from the World War I era.

Some were in such poor shape that they needed extensive repairs or strengthening before they could be loaded, which is why there was a team of dockworkers around the 390-foot Illitch. The wreck was destined to occupy the berth for five months while other Soviet ships continued loading cargoes of all types. In fact, it is probable that some crews would have passed the sunken ship on their way home to Vladivostok, only to return months later and find it was still stuck firmly on the bottom of the river.

Portland was one of the main ports in the Pacific Northwest where Lend-Lease cargoes were loaded in the U.S. program of military aid to the Soviet Union for shipment to Siberia. The USSR was in desperate need of these supplies to feed its population and equip the army fighting the German forces on the Eastern Front. The Ilitch was one of hundreds of Soviet ships that called on Portland during the war.

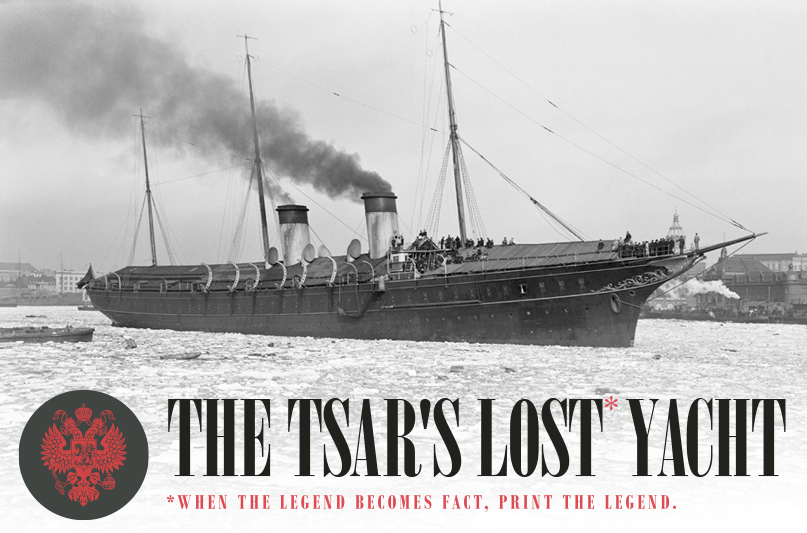

This ship from the Black Sea with the look of a grand passenger liner in the Victorian style must have been an exotic site on the Portland waterfront compared to the functional working vessels moored around it. Barber had previously noted that this was not a typical cargo vessel, writing: “She had a clipper bow with a long bowsprit, and her masks and stacks were set at rakish angles.” Unfortunately, he failed to take a photograph before it sank, an error he must have regretted.

Being a dedicated newspaper man, he began making amends by gathering more information to give this story more interest. With a narrow beam of 45 feet, a large accommodation block, and limited cargo capacity of only 500 tons, it was barely worth traveling 5,000 miles across the Pacific. Perhaps it was sent as a symbol of Russia’s need for aid, like the small craft that helped out during the retreat from Dunkirk. It had been re-fitted with gun turrets, but would not have been able to put up much of a fight. Now its fate was sealed without a single shot being fired.

Hoping to learn more, Barber asked around the docks for details. This was how he heard the rumor that the Illitch had once been the personal yacht of the Tsar Nicolas II.

The workers who had been installing some new cargo winches on deck and extra bunks below decks confirmed that it still had all the comforts of a luxury hotel with the walls lavishly paneled and decorated. The elegant passenger rooms were partitioned off and were not accessible by the wartime crew.

Every ship has a builder’s plaque on the bridge, with name and date of launch. Barber was informed this ship had been built in Dumbarton, Scotland, in 1895 and added this to his notes. This is contradicted by two reliable sources that state it was built in Germany—a curious error considering how much trouble the ship caused.

I decided to do some research on the web and easily found a couple of sites full of information about the Tsar’s real yacht, the magnificent Standart — a 5,557-ton vessel that was 401 feet long and 50 feet wide.

It was built in Copenhagen in 1895 with two funnels and three masts. Standart was the largest, most luxurious private ship ever built until the late 20th century and was reported to have a crew of 260 including over a hundred servants and a brass band.

The Tsars were the absolute rulers of Russia and lived in unparalleled luxury until the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. The entire royal family—the last of the Romanovs—was eventually executed on the order of Lenin. Their magnificent yacht was converted into a minelayer and renamed the Marti. It fought the Germans on the Baltic Sea in World War II and was not scrapped until 1963.

That was on the other side of the world from Portland, but the dimensions and description of the Illitch match almost perfectly with the Standart. Add the fact that it was launched as the Emperor Nicholas II and probably renamed after Vladimir Ilyich Lenin during the Russian Revolution, and it’s easy to see how the ships’ histories could have become blurred.

The Illitch‘s origins were likely similarly luxurious, but still a mystery.

The idea that it was the Tsar’s yacht could have emerged after the name was changed when it was a luxurious ferry or excursion ship on the Black Sea, a working vessel in Siberia, or a world away in Portland, Oregon. Barber mentioned this rumored royal connection in his first report, and continued to follow the saga, which dragged on until the end of the year.

Regardless of its age or history, the Illitch was now an anonymous wreck and a problem that had to be solved as quickly as possible.

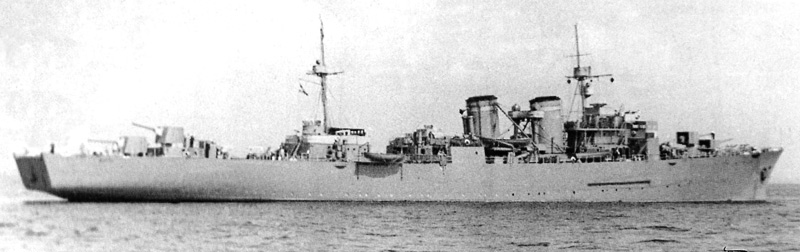

Two hard-hat divers from Devine & Zimmerman arrived by noon and began diving on the wreck in the afternoon. They recovered the body of the cook, which was taken to the city morgue. Coincidentally, the sinking also produced another corpse, that of 49-year-old Joseph Ricchie, who had fallen into the river from the drydock a week before.

The divers returned the next day to clean up the welding leads, cables, and ropes that had slid from the ship’s deck. They then inspected the port side of the hull to look for the cause of the sinking. The divers reported the bottom looked in reasonable condition, while the starboard side was buried in the mud. So that was as far as the investigation into the accident could go, and no cause was ever identified. The most important task was to stop the wreck from sliding under the drydock.

Within five days, a piledriver arrived to install several “dolphins”—clusters of three piles lashed together to form a stable tripod. Wire cables were run from the wreck to the dolphins and winched tight to hold the hull in place temporarily. By the end of the week, many officials had arrived to represent stakeholders; including the Army Engineers, the port, insurers, shipping agent, Russian consulate, etc. But there was no agreement on how to proceed until July 8 when Captain Ivan Sergeiv signed papers to release the craft. “Just what this means is as yet not clear,” Barber pointed out.

On July 14, he wrote that the Army Engineers’ office had received clearance from Washington D.C. to move ahead with the salvage. The contract was opened for bidding for just two weeks until the bids were opened on August 1. Only two companies showed any interest, and when the work finally began at the end of October, they were not mentioned. Instead, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were in charge. By this point, it had been decided that the Illitch was not worth re-floating, even to use the bare hull as a barge.

Larry noted that Captain. J.L. Tooker, a veteran salvage master, was supervising the work, aided by a few of his expert team whom salvaged the famous French trans-Atlantic liner S.S. Normandie in New York Harbor. Normandie was one of the last great ocean liners that was interned in the USA after Germany occupied France in 1939. When the U.S. declared war on Germany, the ship was being converted into a troopship when it caught fire while moored during February of 1942. It rolled over from the weight of water pumped into it by fireboats.

The Normandie laid on the bottom for a year and a half, until it was righted in August 1943. The ship was found to be beyond repair and was broken up and scrapped in 1946.

To expedite the work on the Illitch, Captain Tooker was given the use of the government’s giant derrick barge Cairo, which had been sent to Portland from the Gulf Coast to assist the Kaiser shipyards. It had found a second life loading steam locomotives onto Soviet ships under the Lend-Lease program. By the end of October, the wreck was surrounded by support vessels large and small, with a wide array of equipment on the dock.

Tooker hired eight divers, who each had their own team of helpers to supply their air and ensure their safety, their task was to cut up the submerged ship where it laid. They began cutting through the ship with torches burning a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen gases. On October 21, Barber filed his eighth column on the saga. After describing the process of underwater demolition that was slowly dismantling the ship, he turned to the derrick barge to fill out the story. The mighty Cairo was reputed to be one of the largest floating cranes in the world with a capacity in excess of 160 tons.

“The big Cairo in itself is one of the nation’s most interesting vessels. It is a huge steel barge upon which is mounted a tremendous A-frame, complete quarters for its crew, a machine shop, numerous power units, and all the gadgets that go to make it one of the most formidable lifting units of its kind.

“It was built in 1929 to construct the lower Mississippi levees and then sported a 240-foot boom and a 7.5 cubic yard clamshell bucket. Three years ago, the War Shipping Administration towed the dredge to New York and converted it into a derrick barge to be lend-leased to the British government for the removal of sunken ships in Egypt, but the British failed to take it away.

More than a year ago, the WSA started the Cairo to Portland. After it was nearly wrecked in a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, it was drydocked in New Orleans for installation of a raked bow to improve towing qualities. It finally arrived here after a hectic voyage (via the Panama Canal). The crew ranges from 16 to 22 men. The main fall block stands 8 feet high and weighs 12 tons. It takes something like that to pick up sections of sunken ships like the ill-fated Illitch.”

Through November 1944, the Illitch was cut, reduced to a pile of scrap (sold for $2.27 per ton) and hauled away to feed the steel mills. On December 1, Barber’s final report ran with a description of the last large lift for the Cairo, “a great unwieldy stern section, which included the stern frame, rudder, propeller and stern plate, as well as a gun mount. The piece towered about 60 feet in the air and was estimated to weight about 150 tons, according to Captain J.L. Tooker.”

This scene is the subject of one of Barber’s best wartime news photos and marked the sad end of this fine old ship and all the history it had lived through. As for the hand-carved walnut paneling and fine fixtures in the first-class passenger suites, if they were not pulled off by the current and swept downriver, they would have been burnt off the steel plate onshore.